Updated on January 23, 2026

What is Voltage? The Definitive 2026 Guide

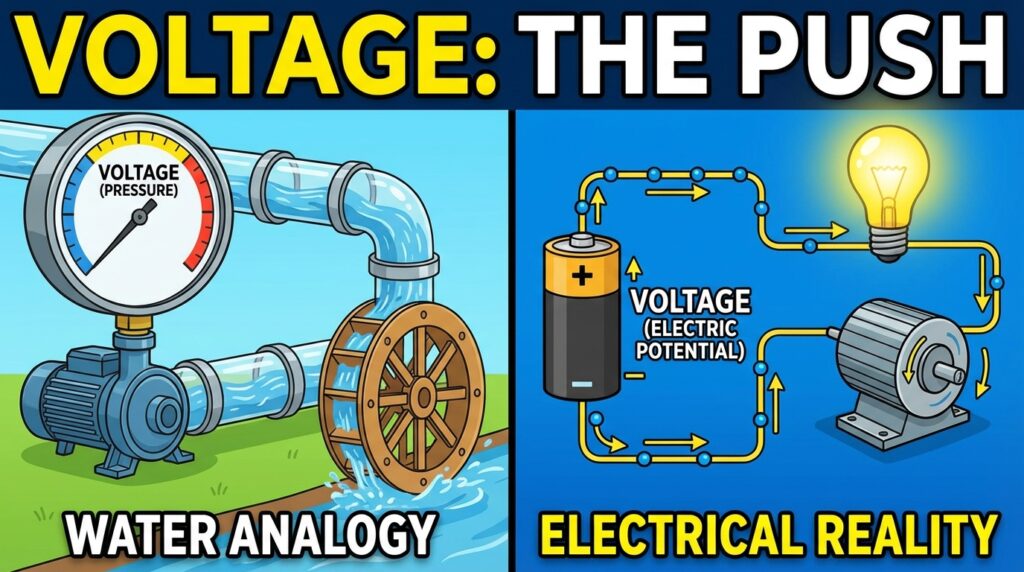

Imagine electricity is like water flowing through a pipe. In this analogy, voltage is the pressure pushing that water. Technically, it’s the electric potential difference or the “push” a power source exerts on electrons (the electric current) to make them move through a circuit and do useful work, like lighting a bulb or running a motor.

Bottom line: Voltage = Pressure. It’s measured in volts (V), named after the Italian physicist Alessandro Volta (1745-1827), who invented the voltaic pile, the forerunner to the modern batteries we use today.

Historically, voltage was also known as electromotive force (EMF). For this reason, in foundational formulas like Ohm’s Law, you’ll see voltage represented by the symbol E (for Electromotive force) or, more commonly today, with a V.

The Core Relationship: Voltage, Current, and Resistance (Ohm’s Law)

To truly get a handle on electricity, you have to understand the interplay between its three fundamental components. The water analogy is still the clearest way to picture it:

- Voltage (V): This is the water pressure. The higher the water tank, the greater the pressure.

- Current (I): This is the flow rate of the water moving through the pipe (measured in amps).

- Resistance (R): This is any narrowing in the pipe. A thinner pipe offers more resistance and restricts the flow rate.

These three are forever linked by Ohm’s Law, the most important formula in electronics: V = I × R (Voltage equals Current times Resistance). This tells us that to push a certain amount of electrons (current) through a conductor that opposes its flow (resistance), we need a specific amount of force (voltage).

AC vs. DC Voltage: What You Need to Know

Voltage isn’t a one-size-fits-all deal. There are two main types, and knowing the difference is crucial for both safety and preventing damage to your electronics. In 2026, this distinction remains the bedrock of all electrical systems.

| Characteristic | Alternating Current (AC) | Direct Current (DC) |

|---|---|---|

| Symbol | V~ or VAC | V⎓ or VDC |

| Source | Power plant generators. This is what comes out of your wall outlets. | Batteries, solar panels, power adapters (chargers). |

| Electron Flow | Periodically reverses direction (60 times per second in the US). Its waveform is a sine wave. | Flows in a single, constant direction, from the negative to the positive terminal. |

| Polarity | No fixed polarity (the ‘Hot’ and ‘Neutral’ wires alternate roles). | Has a fixed and clearly defined polarity (a positive + and a negative – terminal). |

| Common Uses | Major appliances, lighting, industrial motors. Standard in the US is 120V. | Smartphones, laptops, cars, flashlights, internal electronic circuits. |

It’s important to note that many devices we plug into an AC wall outlet (like your laptop or phone charger) use an internal rectifier or power supply to convert the AC voltage to the DC voltage their delicate electronic circuits require.

Understanding Potential Difference

People often use “voltage” and “potential difference” interchangeably, and for everyday purposes, that’s fine. But if you want to be precise, the potential difference is the cause, and voltage is the measurement of that cause.

It’s the difference in electrical charge between two points in a circuit (like the two terminals on a battery or the two slots in an outlet). This imbalance creates the “drive” for electrons to move and try to balance the charge. The bigger the difference, the more “potential” there is to do work.

- A standard AA battery has a potential difference of 1.5V.

- A typical car battery has 12V.

- A standard household outlet in the US has 120V.

Higher voltage means a greater capacity to “push” electrons through a circuit, and therefore, a greater capacity to perform work.

How to Safely Measure Voltage with a Multimeter

As a tech enthusiast and DIYer, measuring voltage is a daily task for troubleshooting gadgets and circuits. It’s a job that demands absolute focus and respect for electricity because, unlike other measurements, it’s done while the circuit is live.

Here are the basic steps for a safe measurement:

- Safety Gear: Always use insulated electrician’s gloves and ensure your multimeter and its probes are in perfect condition and rated for the voltage you’re measuring (e.g., CAT III or CAT IV).

- Select the Right Function: Turn the dial on your multimeter to the correct voltage setting. Use V~ (or VAC) for alternating current (wall outlets) and V⎓ (or VDC) for direct current (batteries).

- Connect the Probes: The black (negative) lead always goes into the COM jack. The red (positive) lead goes into the jack marked with a V (often shared with Ω and mA).

- Measure in Parallel: To measure voltage, you must place the probes in parallel with the component. For example, to measure a wall outlet, you insert one probe into each slot. You do not need to break open the circuit.

- Take the Reading: Being very careful not to touch the metal tips of the probes, make firm contact with the points you’re measuring and read the value on the multimeter’s screen.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) about Voltage

What happens if voltage is too high or too low?

Both scenarios are bad news. An overvoltage (higher than normal voltage) can fry the electronic components of a device. An undervoltage or “brownout” (lower voltage) can prevent devices from working correctly or cause motors to overheat as they try to compensate for the lack of “push.”

Is it the voltage that shocks you?

This is a super common question. The actual damage from an electric shock is caused by the current (the amps) passing through your body. However, you need sufficient voltage to “push” that lethal current through the high resistance of human skin. That’s why touching a 1.5V AA battery does nothing, but touching a live 120V wire can be fatal.

Can I use a 230V appliance in a 120V outlet?

It generally won’t work correctly, if at all. A device designed for 230V (common in Europe) will receive only half the pressure it needs from a 120V US outlet. It will be severely underpowered. The reverse is far more dangerous: plugging a 120V device into a 230V outlet will almost instantly destroy it and poses a serious fire risk. For travel, you need a specific step-up or step-down transformer.

What’s the difference between “line voltage” and “low voltage”?

In a home context, line voltage refers to the standard power from your outlets, typically 120V or 240V for large appliances like dryers. Low voltage refers to systems that use a transformer to step that power down to a much safer level, usually 12V or 24V. This is common for things like landscape lighting, doorbell circuits, and thermostats, where the risk of electric shock needs to be minimized.